Dayak people

|

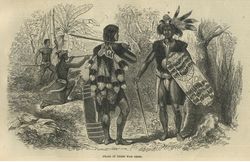

| Dayaks in their war dress, 1864 |

| Total population |

|---|

| 6 million (est.2009)[1][2] |

| Regions with significant populations |

| Indonesia, Malaysia, Brunei |

| Languages |

|

Dayak languages |

| Religion |

|

Predominantly Catholic (81%), Protestant (3%), Orthodox (1%), Lutheran (0.5%), Kaharingan-Hinduism (7%), Islam (2%), Atheist (0.5%). |

| Related ethnic groups |

|

Ahe, Banjar, Barito, Benuaq, Berawan, Bidayuh, Bukitan, Dumpas, Dusun, Iban, Iban Mualang, Iban Embaloh, Ida'an, Illanun, Kadazan, Kayan, Kedayan, Kelabit, Kendayan, Kenyah, Kejaman, Kwijau, Lun Bawang, Lun Dayeh, Lotud, Maloh, Mangka'ak, Maragang, Minokok, Murut, Ngaju, Penan, Punan Ba, Rajang, Rumanau, Rungus, Selakau, Sepan, Taman, Tambanuo, Tanjung, Tidong, Ukit, etc |

The Dayak or Dyak (pronounced /ˈdaɪ.ək/) are a people indigenous to Borneo.[3] It is a loose term for over 200 riverine and hill-dwelling ethnic subgroups, located principally in the interior of Borneo, each with its own dialect, customs, laws, territory and culture, although common distinguishing traits are readily identifiable. Dayak languages are categorised as part of the Austronesian languages in Asia. The Dayak were animist in belief; however many converted to Christianity, and some to Islam more recently.[4] Estimates for the Dayak population range from 2 to 4 million.[1][2]

Contents |

History of the Dayak People

The consensus interpretation in modern anthropology is that nearly all indigenous peoples of South East Asia, including the Dayaks, are descendants of a larger Austronesian migration from Asia, thought to have settled in the South East Asian Archipelago some 3,000 years ago. The first populations spoke closely-related Austronesian languages, from which Dayak languages are traced. About 2,450 years ago, metallurgy was introduced; it later became widespread.

The main ethnic groups of Dayaks are the Bakumpai and Dayak Bukit of South Kalimantan, The Ngajus, Baritos, Benuaqs of East Kalimantan, the Kayan and Kenyah groups and their subtribes in Central Borneo and the Ibans, Embaloh (Maloh), Kayan, Kenyah, Penan, Kelabit, Lun Bawang and Taman populations in the Kapuas and Sarawak regions. Other populations include the Ahe, Jagoi, Selakau, Bidayuh, and Kutais.

The Dayak people of Borneo possess an indigenous account of their history, partly in writing and partly in common cultural customary practices. In addition, colonial accounts and reports of Dayak activity in Borneo detail carefully-cultivated economic and political relationships with other communities as well as an ample body of research and study considering historical Dayak migrations. In particular, the Iban or the Sea Dayak exploits in the South China Seas are documented, owing to their ferocity and aggressive culture of war against sea dwelling groups and emerging Western trade interests in the 19th and 20th centuries.

During World War II, the Japanese occupied Borneo and treated all of the indigenous peoples poorly - massacres of the Malay and Dayak peoples were common, especially among the Dayaks of the Kapit Division[5]. Following this treatment, the Dayaks formed a special force to assist the Allied forces. Eleven United States airmen and a few dozen Australian special operatives trained a thousand Dayaks from the Kapit Division to battle the Japanese with guerilla warfare. This army of tribesmen killed or captured some 1,500 Japanese soldiers and were able to provide the Allies with intelligence vital in securing Japanese oil fields.[6]

Coastal populations in Borneo are largely Muslim in belief, however these groups (Ilanun, Melanau, Kadayan, Bakumpai, Bisayah) are generally considered to be Islamized Dayaks, native to Borneo, and heavily influenced by the Javanese Majapahit Kingdoms and Islamic Malay Sultanates.

Traditional headhunter culture

In the past the Dayak were feared for their ancient tradition of headhunting practices. After conversion to Islam or Christianity and anti-headhunting legislation by the colonial powers the practice was banned and disappeared, only to resurface in the late 90s, when Dayak started to attack Madurese emigrants in an explosion of ethnic violence.[7]

Agricultural

Traditionally, Dayak agriculture was based on swidden rice cultivation. Agricultural Land in this sense was used and defined primarily in terms of hill rice farming, ladang (garden), and hutan (forest). Dayaks organised their labour in terms of traditionally based land holding groups which determined who owned rights to land and how it was to be used. The "green revolution" in the 1950s, spurred on the planting of new varieties of wetland rice amongst Dayak tribes.

The main dependence on subsistence and mid-scale agriculture by the Dayak has made this group active in this industry. The modern day rise in large scale monocrop plantations such as palm oil and bananas, proposed for vast swathes of Dayak land held under customary rights, titles and claims in Indonesia, threaten the local political landscape in various regions in Borneo. Further problems continue to arise in part due to the shaping of the modern Malaysian and Indonesian nation-states on post-colonial political systems and laws on land tenure. The conflict between the state and the Dayak natives on land laws and native customary rights will continue as long as the colonial model on land tenure is used against local customary law. The main precept of land use, in local customary law, is that cultivated land is owned and held in right by the native owners, and the concept of land ownership flows out of this central belief. This understanding of adat is based on the idea that land is used and held under native domain. Invariably, when colonial rule was first felt in the Kalimantan Kingdoms, conflict over the subjugation of territory erupted several times between the Dayaks and the respective authorities.

Religion

The Dayak indigenous religion is Kaharingan, a form of animism which, for official purposes, is categorized as a form of Hinduism in Indonesia. The practice of Kaharingan differs from group to group, and for example in some religious customary practices, when a noble (kamang) dies, it is believed that the spirit ascends to a mountain where the spirits of past ancestors of the tribe reside.[8] On particular religious occasions, the spirit is believed to descend to partake in celebration, a mark of honour and respect to past ancestors and blessings for a prosperous future.

Over the last two centuries, some Dayaks converted to Islam, abandoning certain cultural rites and practices. Christianity was introduced by European missionaries in Borneo. Religious differences between Muslim and Christian natives of Borneo has led, at various times, to communal tensions. Relations, however between all religious groups are generally good.

Muslim Dayaks have however retained their original identity and kept various customary practices consistent with their religion.

An example of common identity, over and above religious belief, is the Melanau group. Despite the small population, to the casual observer, the coastal dwelling Melanau of Sarawak, generally do not identify with one religion, as a number of them have Islamized and Christianised over a period of time. A few practise a distinct Dayak form of Kaharingan, known as Liko. Liko is the earliest surviving form of religious belief for the Melanau, predating the arrival of Islam and Christianity to Sarawak. The somewhat patchy religious divisions remain, however the common identity of the Melanau is held politically and socially. Social cohesion amongst the Melanau, despite religious differences, is markedly tight.

Despite the destruction of pagan religions in Europe by Christians, most of the people who try to conserve the Dayak's religion are missionaries. For example Reverend William Howell who has contributed to the Sarawak National Gazette. His contributions were also compiled in the book The Sea Dayaks and Other Races of Sarawak.

Society

Kinship in Dayak society is traced in both lines. Although, in Dayak Iban society, men and women possess equal rights in status and property ownership, political office has strictly been the occupation of the traditional Iban Patriarch. Overall Dayak leadership in any given region, is marked by titles, a Penghulu for instance would have invested authority on behalf of a network of Tuai Rumah's, and so on to a Temenggung or Panglima. It must be noted that individual Dayak groups have their social and hierarchy systems defined internally, and these differ widely from Ibans to Ngajus and Benuaqs to Kayans.

The most salient feature of Dayak social organisation is the practice of Longhouse domicile. This is a structure supported by hardwood posts that can be hundreds of metres long, usually located along a terraced river bank. At one side is a long communal platform, from which the individual households can be reached. The Iban of the Kapuas and Sarawak have organized their Longhouse settlements in response to their migratory patterns. Iban Longhouses vary in size, from those slightly over 100 metres in length to large settlements over 500 metres in length. Longhouses have a door and apartment for every family living in the longhouse. For example, a Longhouse of 200 doors is equivalent to a settlement of 200 families.

Headhunting was an important part of Dayak culture, in particular to the Iban and Kenyah. There used to be a tradition of retaliation for old headhunts, which kept the practice alive. External interference by the reign of the Brooke Rajahs in Sarawak and the Dutch in Kalimantan Borneo curtailed and limited this tradition. Apart from massed raids, the practice of headhunting was then limited to individual retaliation attacks or the result of chance encounters. Early Brooke Government reports describe Dayak Iban and Kenyah War parties with captured enemy heads. At various times, there have been massive coordinated raids in the interior, and throughout coastal Borneo, directed by the Raj during Brooke's reign in Sarawak. This may have given rise to the term, Sea Dayak, although, throughout the 19th Century, Sarawak Government raids and independent expeditions appeared to have been carried out as far as Brunei, Mindanao, East coast Malaya, Jawa and Celebes. Tandem diplomatic relations between the Sarawak Government (Brooke Rajah) and Britain (East India Company and the Royal Navy) acted as a pivot and a deterrence to the former's territorial ambitions, against the Dutch administration in the Kalimantan regions and client Sultanates.

Metal-working is elaborately developed in making mandaus (machetes - 'parang' in Indonesian ). The blade is made of a softer iron, to prevent breakage, with a narrow strip of a harder iron wedged into a slot in the cutting edge for sharpness. In headhunting it was necessary to able to draw the parang quickly. For this purpose, the mandau is fairly short, which also better serves the purpose of trailcutting in dense forest. It is holstered with the cutting edge facing upwards and at that side there is an upward protrusion on the handle, so it can be drawn very quickly with the side of the hand without having to reach over and grasp the handle first. The hand can then grasp the handle while it is being drawn. The combination of these three factors (short, cutting edge up and protrusion) makes for an extremely fast drawing-action. The ceremonial mandaus used for dances are as beautifully adorned with feathers, as are the costumes. There are various terms to describe different types of Dayak blades. The Nyabor is the traditional Iban Scimitar, Parang Ilang is common to Kayan and Kenyah Swordsmiths, and Duku is a multipurpose farm tool and machete of sorts.

Politics

Dayaks in Indonesia and Malaysia have figured prominently in the politics of these countries. Organised Dayak political representation in the Indonesian State first appeared in Kalimantan during the Dutch Administration, in the form of the Dayak Unity Party (Parti Persatuan Dayak) in the 30s and 40s. Feudal Dayak Sultanates of Kutai, Banjar and Pontianak figured prominently prior to the rise of the Dutch Colonial rule.

Dayaks in Sarawak in this respect, compare very poorly with their organised brethren in Kalimantan, partly due to the personal fiefdom that was the Brooke Rajah dominion, and possibly to the pattern of their historical migrations from the Kalimantan Regions to the then pristine Rajang Basin. Political circumstances aside, the Dayaks in Kalimantan actively organised under various associations beginning with the Sarekat Dayak established in 1919, to the Parti Dayak in the 40s, and to the present day, where Dayaks occupy key positions in government.

In Sarawak, Dayak political activism had its roots in the SNAP (Sarawak National Party) and Pesaka during post independence construction in the 1960s. These parties shaped to a certain extent Dayak politics in the State, although never enjoying the real privileges and benefits of Chief Ministerial power relative to its large electorate.

Under Indonesia's transmigration programme, settlers from densely-populated Java and Madura were encouraged to settle in the Kalimantan provinces, but their presence was, and still is, resented by Dayaks, Banjars and local Malays. The large scale transmigration projects initiated by the Dutch and continued by the current national government, caused widespread breakdown in social and community cohesion during the late 20th Century. In 2001 the Indonesian government ended the gradual Javanese settlement of Kalimantan that began under Dutch rule in 1905.

From 1996 to 2003 there were systemic and violent attacks on Indonesian Madurese settlers, including mass executions of whole Madurese transmigrant communities. The violence culminated in the Sampit conflict in 2001 which saw more than 500 deaths in that year alone. Eventually, order was restored by the Indonesian Military but this was late in application.

See also

- Krio Dayak people and their language

- Iban people and their Iban language

- Meratus Dayak

- Meratus language

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 http://concise.britannica.com/ebc/article-9029561/Dayak

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 WWF - Borneo people

- ↑ Ethnologue report for ISO 639 code: day

- ↑ http://coombs.anu.edu.au/SpecialProj/ASAA/biennial-conference/2006/Chalmers-Ian-ASAA2006.pdf

- ↑ http://pariwisata.kalbar.go.id/index.php?op=deskripsi&u1=1&u2=1&idkt=4

- ↑ 'Guests' can succeed where occupiers fail, November 9, 2007

- ↑ [1]

- ↑ Nancy Dowling (1992). "Javanization of Indian Art" (– Scholar search). Indonesia (Indonesia, Vol. 54) 54: 117–138. doi:10.2307/3351167. http://cip.cornell.edu:80/Dienst/UI/1.0/Summarize/seap.indo/1106967528.

Further reading

- Victor T King, Essays on Bornean Societies (Hull/Oxford, 1978).

- Benedict Sandin, The Sea-Dayaks of Borneo before White Rajah Rule (London 1967).

- Eric Hansen , Stranger in the Forest: On Foot Across Borneo, (Penguin, 1988), ISBN 0-375-72495-8.

- Norma Youngberg, The Queen's Gold (TEACH Services, 2000)

- Judith M. Heimann, The Airmen and the Headhunters: A True Story of Lost Soldiers, Heroic Tribesmen and the Unlikeliest Rescue of World War II, (Harcourt, 2007), ISBN 978-0-15-101434-7

- Secrets of the Dead: The Airmen and the Headhunters, PBS. November 11, 2009

External links

- www.worldmessenger.ning.com- social networking site run by Urban Dayaks Generation

- www.dayakology.com - a site run by Dayaks

- Assessment for Dayaks in Malaysia

- Tribal peoples are fighting huge hydro-electric projects that are carving up the island's rainforest

- The J. Arthur and Edna Mouw papers at the Hoover Institution Archives focuses on the interaction of Christian missionaries with Dayak people in Borneo.